Delving into the Complexity of Unmasking Safely

Based on the webinar by Jade Farrington & Kieran Rose, The Autistic Advocate

Paid subscribers can download this article as an ebook at the bottom of this post or from the pdf downloads catalogue.

As part of Neurokindred’s Thriving Autistically online wellbeing festival, we spent two hours discussing masking and answering questions from the Autistic audience.

The event wasn’t recorded, so the article below is a curated and edited version.

Kieran began by conceptualising masking; busting some of the myths that surround it; and looking at why we do it. Jade then delved into how we might be able to start unmasking safely, and considered why it’s not as simple as a lot of the mainstream narratives suggest.

The webinar drew on our previous work, training, and resources, as well as adding new context, content, and practical application.

The piece below is necessarily long (more than 10,000 words). Masking is a topic that is frequently over-simplified to the point of being reduced to a caricature, and this all needs unpicking and recontextualising before getting to the idea of unmasking.

Masking touches on a range of experiences around stigmatisation, oppression, abuse and poor mental health, so please be mindful of this before reading.

The Complexity of Unmasking Safely

We can’t talk about unmasking without understanding what masking is.

An iceberg is often used as a visual reference for behaviour, with the peak of the iceberg floating up above the sea, and underneath there’s much more going on. This is what’s happening with masking. We often recognise the surface behaviours and talk about those a lot, but we don’t tend to recognise the systems underneath.

So we have three important questions: What is masking? Why does it happen? And what’s the impact of it?

We had limited time for our talk, so some of these narratives are touched on superficially. Despite being a long piece, this is still only an introduction into a deeper topic. Everything that happens to an Autistic person is an individual process, so it’s worth looking at the bits that interest you in more depth and personalising it for yourself.

So what is masking? It’s not what most people think it is. Most content presents masking as entering a social situation and putting on a neurotypical mask in an attempt to fit in. You then leave the situation, take off the mask, and go back to being who you were before.

Two narratives explain that behaviour. The first is ‘impression management’ which is an academic term which can be explained by context switching. We all wear different hats for different occasions. We all put on slightly different personas depending on the context we’re in. You might do that in minimal ways that you don’t recognise - or in big ways that you really do. That isn’t masking, but an aspect, and it’s something all human beings engage in. We all do things slightly differently around other people. When we’re talking about masking, we’re taking the next step. We move into something called ‘identity management’.

When we think about masking, we have to think about what’s happening in a social context, but also what’s happening in our lives and our past because of our identities. We can’t properly consider social context without thinking about identity. Our identities are integral to how we present as human beings. Think about what happens to Autistic identities over time, and about how the things that happen to us can shape who we are and how we show up in certain spaces.

Throughout our developmental years, Autistic people frequently experience a persistent lack of felt safety, consistent invalidation, correction and pathologisation across every domain of being. Masking can be framed as a survival response to this.

‘Autistic masking’ is the term the community has been using for years now, and other names tend to come from academic research. But there’s another concept, ‘projecting acceptability’, which is about giving a version of yourself to others that they find acceptable.

This survival response exists to manage the risk of rejection, punishment or harm - three things that are quite common in the lives of Autistic people. It’s about being predictable to others in unsafe and neuronormative environments.

When you have a lack of felt safety in most environments you enter, it’s natural to look for predictability to become an anchor in those places, to make them a little bit more concrete. This might not make it safe, but making it more predictable means you can anticipate what’s going to happen. Known responses from others - even unsafe responses - can feel safer than uncertainty.

So masking isn’t just fitting in, or putting on this neurotypical mask. It can look like lots of different things and your mask can develop in lots of different ways, depending on your personal context and what’s going on for you.

The persona you put on in different spaces - or whether you have the same or a similar persona in all sorts of spaces - might be driven by a lack of safety and by not feeling like you belong.

The impact of this is linked to a trauma narrative. In the Autistic community there are huge rates of exhaustion, Autistic burnout, poor mental health, and increased vulnerability to trauma and suicidality. All kinds of experiences feature here, including disconnection from your internal, physical, emotional and psychological self, and fractured identity development.

One of the things missing from the mainstream narrative around masking is stigma. Stigma impacts everyone, but marginalised people are impacted particularly deeply.

According to the American Psychiatric Association, stigma is “the negative social attitude attached to a characteristic of an individual that may be regarded as a mental, physical or social deficiency.” This is written in a problematic way, but stigma implies social disapproval. It’s about other people’s perceptions of a particular person or group of people, and it can lead to unfairly discriminating against and excluding them.

There is an ecology of stigma wrapped around Autistic people.

Environments we enter and interactions we have with other people are soaked in stigma. And that’s not just happening in social situations. Our families, our support networks, and the systems we engage in are all soaked in a stigma about Autistic people and Autistic behaviours, whether they know that we are Autistic or not.

One way we can look at stigma is to think about the history of autism (Kieran runs an in-depth training course framed around this). The concept of autism has been around for about 120 years. There’s lots of research and lots of people talking about autism, but very few talking about Autistic people.

This matters because there’s a difference between ‘autism’ and ‘being Autistic’. The first is a medicalised construct in a book that’s been developed over a century. The second is about the actual day to day lives of a certain group of people and what that means for them.

We choose to focus on Autistic experience because we think it’s more important than looking at this abstract behaviourist term of ‘autism’ - a problematic category that people put us in. Why is it problematic? Because it’s been developed in problematic ways by lots of problematic people with problematic views. (We use that word a lot).

One thing that’s missing from the autism narrative is highlighted in Chinua Achebe’s quote, based on a Nigerian proverb: “Until Lions have their historians, tales of the hunt shall always glorify the hunter.” Autistic people have been denied the ability to contribute to our own narrative.

Things have begun to shift a little in the last 10 to 15 years, as more and more Autistic people have utilised social media and accessed research. Historically, it’s all been about non-Autistic people (or people who perceive themselves as non-Autistic) observing Autistic people and making judgments based on their ideas of what is and isn’t ‘normal’. Ironically, we’re told all the time that there is no such thing as normal. But in psychology and psychiatry, the idea that there are people who have deficits also creates the perception that there’s a person who you have deficits in relation to - a perfect person who supposedly exists.

All of the diagnoses in the DSM are considered to be ways in which humans can be imperfect, which is really quite judgmental. Eugenics is a massive part of this narrative, and a huge driving force behind it. The idea of a perfect person, and imperfect people, is a eugenics narrative. This isn’t how evolution or science work, but the concept has become embedded regardless.

The recent shift has come from Autistic people barging their way into academia, and activists and advocates online and in public spheres pushing back against these narratives around us. In pockets of autism research, there’s been a lightbulb moment. They’ve realised the fundamental flaw over the last century: Autistic people haven’t actually been asked what we would like; what goes on in our bodies; or what we think about our experiences. It’s all been from the outside, looking in through the lens of disorder, and making judgments about us.

Critical reflection is starting to appear in autism research, and there is more co-production. Autistic researchers are leading some studies, and the narrative has started to shift a little.

We come into community spaces, such as the one where we delivered this talk, and it’s a safer space because we’re all talking to similar themes. And then, suddenly, someone like Donald Trump says awful things, and we realise our safer bubbles are actually quite small.

So this shift isn’t happening in huge ways, but in tiny ways which are still meaningful, and will fundamentally impact change. But we’re still surrounded by a stigmatised narrative. ‘Autism’ is a stigmatised label, and this is where that comes from.

This stigma doesn’t stay in research. It goes out into the public consciousness, into cultural perceptions, and then feeds back into research as well because researchers are part of society and culture. We have a stigmatised academic narrative, and a stigmatised cultural narrative, all feeding people’s perceptions and biases.

Media and cultural representations of Autistic people are generally still white, and mostly male. Things are different in tiny pockets, but representations are usually highly stereotypical. People’s perceptions are being shaped before they even meet us. They look for these characteristics and stereotypes, and make shortcuts in their brains. They use their heuristics to make connections. When they see behaviour that might be recognisable from the TV, that creates a picture of what an Autistic person is - or at least what these stigmatised characteristics are. Some of these characters are Autistic coded, so they’re not out as Autistic, and some are distinctly Autistic. All are problematic representations.

All of this feeds bias and the picture people have in their heads. Within this ecology of stigma we have cumulative and multi-level invalidation and pathologisation. Whether someone knows you’re Autistic or not, they’re still recognising differences in your behaviour. These include how you communicate, sleep, learn, behave, perceive the world, play, move, and more. A full list would cover every domain of what it means to be human.

As an Autistic person, every facet of who you are is potentially up for correction or invalidation or pathologisation in some way because of the history, the cultural belief system, and the idea that there is a ‘normal’.

We could look at the history of ADHD, or the history of bipolar, or any other form of neurodivergence - whether a diagnosis exists for it or not - and find a stigmatising picture that informs how people think humans should be.

Autistic babies are human beings processing sensory information. They might have a reaction which is unexpected, and all of a sudden that invalidation can come in unwittingly. We don’t know what a baby is experiencing, as its only way of communicating might be to cry. We have to guess what’s going on and we might miss lots of reasons as to why they’re distressed or upset.

The same goes for people who don’t develop speech or don’t speak in some way. If non-speakers are not facilitated with meaningful communication then people rely on guesswork, and that guesswork is usually built on biases. It’s all feeding that ecology and swirling around Autistic people. We develop within this ecology, not within a vacuum.

Lots of people seem to think of autism as fixed and concrete, and therefore view Autistic people as fixed and concrete too, but that isn’t how it works. Autistic people develop socially, as do other human beings. We’re surrounded by this potential threat to ourselves, this idea that we are wrong in some way.

Lots of people don’t correct us or invalidate us wittingly. Many do it unwittingly and often with the best intentions, which can be even more dangerous than when people openly treat you badly.

There’s a ‘high masking’ narrative with the idea that some Autistics fit in so well that nobody notices them. It’s true that teachers miss people and diagnosticians need years to diagnose. But bullies find Autistics very quickly, without necessarily even seeing them as an ‘Autistic’ person. The stigma already exists whether the label is attached or not. If masking is what we’re usually told it is, i.e. acting neurotypical, then most of us actually aren’t that good at it.

We might think we’re good at it though, maybe because we’ve had a career, or had a family, or not been recognised as an Autistic person. But people will still have been treating us with a stigmatised lens, because our behaviours are different.

Some Autistics have a different diagnosis. Instead of being seen as an Autistic person, you might be seen as ADHD or bipolar, for example, or you might be seen as having a mental health condition. You might have been treated for mental health conditions instead of being recognised as Autistic, so you’ve been stigmatised through another lens.

Or the labels might be non-medical, such as quirky, weird, needy or hysterical. Some are gender-based, and some are groupings that people just plop us in, because human beings love to categorise. We are picked up as different whether or not we are given the Autistic label.

This is where the notion of ‘high masking’ falls apart. It leans into the problematic idea that there are high functioning and low functioning people. We might not have been recognised as Autistic, but that doesn’t mean that we haven’t been recognised as different. And if we are recognised as different, that usually triggers problematic responses from other people.

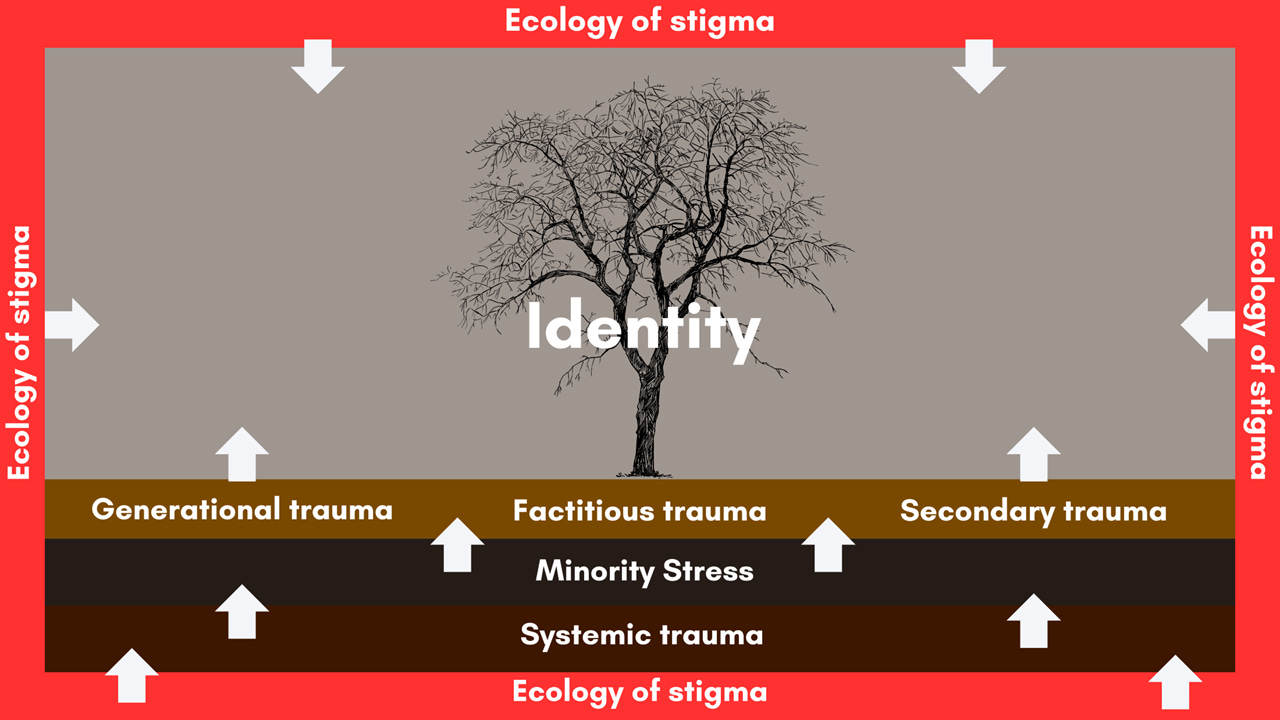

Many systems feed into identity. It can help to think of it like a tree, with different branches and facets. Think about the soil within which your identity grows. Around an Autistic person, we have that ecology of stigma, so that’s the water and nutrients that are being pushed into the soil.

Within the soil are things like stress and different types of trauma, such as generational trauma; factitious trauma (an accumulation of negative experiences which build up over time); and secondary trauma (from supporting other people who have experienced trauma).

And around this, minority stress interacts with who you are. As a minority, there are particular stresses you experience intersectionally, because Autistic people don’t exist in just one way. You may experience different levels of minority stress, prejudice or stigma because of different facets of your identity. A Black, queer, Autistic person who is also physically disabled holds four stigmatised identities, and might be stigmatised and experience stigma for all of these. That causes stress on your body, known as minority stress, which feeds into trauma.

This all feeds into your identity as you develop and grow, so the development of your identity becomes unstable and fractured. The focus is on how to keep yourself safe. Other people’s identities may not be framed around their need for safety, because they might automatically receive it. They won’t experience minority stress or be impacted by prejudice and stigma if their identities mean they lean into what a normative society looks like, and they fit in effectively.

So what does this do to you over the course of your life? You start off as a baby, experiencing external stigma. You might not feel safe, and you might experience trauma. Maybe you experience microaggressions, and have different labels applied to you. People tell you that don’t need the things you actually do, or that you’re overreacting. When you receive those messages consistently, you internalise them. You might experience poor mental health as a result. Masking becomes a theme; you change your behaviours unconsciously; and experience periods of burnout throughout your life.

In older adulthood you’re still experiencing all of the stigma, the lack of safety, and microaggressions. You’re probably carrying around boatloads of trauma, while still being further traumatised in lots of ways, and you still have unmet needs. But on top of it all, you all have an unstable identity wrapped up with internalised stigma, or what we might see as internalised ableism.

There’s a common narrative among late identified Autistic adults where all of a sudden you don’t know who you are. This new information may have hit you like a truck, and you’re left wondering what’s really you and experiencing an unstable identity.

If you have a solid sense of who you are in different circumstances; feel you can be as authentic as you want to be in most situations; and don’t feel unsafe all of the time; then you’re going to have a much stronger core, stable identity. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t shift and move, but it does so in more manageable ways, instead of being built around the need to keep yourself safe and meet the needs of other people all the time. If you regularly need to anticipate how people are going to treat you because that’s historically negative, you’re going to anticipate a lot of negativity as well.

Being unsafe doesn’t necessarily mean being under threat of physical harm. Felt safety fits right in the core as the emotional and psychological experience found in the space between knowing you’re safe and actually feeling safe.

It’s rooted in our interactions, environments, and our unconscious narratives about what those environments mean to us. It’s the quiet, embodied sense that your whole self, including your nervous system, is safe to exist as it is.

How many Autistic people feel like this regularly? How many Autistic people actually feel that your whole self, including your nervous system, is safe to exist as it is? Probably very few. For Autistic people, felt safety is often fleeting at best, and persistently non-existent at worst.

The constant weight of invalidation and stigma and coercion means we rarely experience environments that affirm us fully, even in moments when there’s no immediate threat. The body and brain may not register safety, because history has taught us that danger hides in the every day - things like correction, invalidation, exclusion, ridicule, or the subtle pressures to change who we are. Even if they aren’t explicit, there are implicit pressures on us to do things differently.

We carry that threat with us. When we enter what might be considered a safer environment, it can be hard to interact as if it were safe. This destroys the notion that other people get to choose what a safe environment looks like for us.

For children, this feeling of threat is often magnified at school. Schools are routinely described as safe and nurturing, but for Autistic children they can be the opposite, because they’re designed around neuronormative assumptions that erase Autistic needs. The structure of school demands things like silence, compliance, and conformity. It doesn’t leave space for monotropic processing; sensory safety; alternative communication; or the ability to interact with other human beings in a way that motivates and feels safe and comfortable for everyone.

So within that framework, Autistic children are not only denied felt safety, they’re actively placed in environments where unsafety is the norm. That feeling of unsafety is a massive part of that ecology of stigma, and that’s what has the biggest impact on us.

The historic and academic narratives of masking have confused impression management and context switching for identity management. They’re treating masking as a surface-level behaviour, such as the idea of putting on a disguise and using scripts.

There’s an illusion of choice around all of this. There might be a conscious recognition of what’s going on, but unconsciously your identity has been shaped and framed around all these negative experiences.

Masking isn’t merely part of a social interaction, but a whole embodied experience that remains with you, whether or not you’re with other people. Identity management is far deeper and more pervasive. It’s adapting your entire identity around others’ needs and expectations. But you can’t meet everyone’s needs and expectations in different environments, so your identity fractures in multiple ways and becomes really unstable.

This process can be defined as projecting acceptability - a developmental, unconscious response to cumulative trauma, stigma and a lack of safety by changing, exaggerating or suppressing behaviours. These behaviours are mostly unconsciously projected to meet the expectations and needs of others in order to keep you safe and predictable for them, and therefore them and safe and predictable for you.

Other people have an expectation of you, and when you don’t match up with that expectation that creates unsafety for the other person. You’ve become an unpredictable element in their lives. How you meet their expectations depends on the context of who the person is and what they want or expect from you.

If you’re meeting a stranger for the first time, that might mean you lean into more neutral behaviours. Some Autistic people might not be able to do this. For example, if you have strong ADHD traits, you might move your body a lot. You might talk very quickly. You might not be able to stand still. You might have to do lots of different things, or become distracted quite easily, or switch what you’re paying attention to.

You might not be able to lean into the neutral experience, but you’re still looking for ways to give someone what they expect. Their expectations are shaped by lots of things, and it requires incredible theory of mind to try to predict what someone wants from you. Autistic people use theory of mind to anticipate this, and to think about all the different things that might have shaped that person’s perspectives of you. So the idea of Autistic people lacking theory of mind falls apart with an understanding of masking.

This tends to be done unconsciously through your prediction model. All humans use prediction as an important facet of how we interact. We like to know what’s going to happen, because it helps to balance and control our anxiety. Masking develops as a survival response framed around that predictability. Giving other people a version of yourself that they can anticipate can dominate your whole being and become outwardly who you are.

Predictability equals safety, because when others can read you, you’re less likely to face the harsh consequences of being misunderstood. It might mitigate some of the unsafety that you feel.

This doesn’t just mean acting neurotypical - sometimes it means exaggerating Autistic or other neurodivergent traits so that others won’t doubt your difference. For others, it might mean big, loud behaviours that draw attention, because people might expect that from you. You might be the class clown, the people pleaser, the quiet one, the bullish one. It can look like anything.

Masking can be a combination of all those things happening in different spaces or contexts. It might mean the same version of you in all contexts, leaning into who you are as an individual. Sometimes it might mean acting in ways that make you unsafe, because known harm can feel safer than the uncertainty of not knowing what punishment or rejection might come next.

Conscious, surface behaviours are a minimal part of what’s going on. Masking isn’t a deliberate performance that you put on. It’s something that embeds itself in your brain and body over years. Every time you’re corrected, dismissed or punished, your nervous system begins to anticipate danger and adapts automatically.

This fractured and unstable identity where you are shaped around other people’s expectations and needs can leave you with a poor relationship with your internal self.

Autistic people often struggle with interoceptive processes, such as not knowing when to go to the toilet, or when you’re full. Autistic people naturally have sensory processing differences which vary from person to person, but this can also be contributed to by learning not to listen to your body, because listening to it means ignoring what other people are expecting from you at times.

This links into the narrative we have around alexithymia, and the misaligned relationship with our emotional self. It’s contributed to by the ecology of stigma and invalidation; by the fact that people tell us that we overreact; that we shouldn’t be feeling a certain way; or that we’re feeling the emotion wrong.

Most of the language used around emotion and internal sensations is centred on non-Autistic experiences of what’s going on in our emotional, physical and sensory body. If the words aren’t right for many Autistic people; the way we talk about what’s being experienced doesn’t fit; and you’re invalidated for those experiences; you learn to stop listening to yourself. Instead, you model yourself on what other people expect from you as best you can.

The energy Autistic people pour into existing is disproportionate in comparison to people who aren’t marginalised or stigmatised. Shaping your identity like this is exhausting. Existing and interacting on a day to day basis is exhausting. When that builds up over time, when your needs aren’t met, then you burn out, and your ability to mask will probably fall away. That, in turn, leads to poorer mental health. The continuation of trauma can lead people to be put into harmful situations such as abusive relationships.

For children there’s school-induced trauma, known in the UK by the victim-blaming labels of school refusal and emotionally based school avoidance (EBSA). A similar experience can be applied to work as well, where many Autistic people struggle and become more and more exhausted over time. They may reach the point where they can’t go anymore, or get fired.

This narrative can hinder people’s identification as Autistic, and also prevent other people from seeing you as an Autistic person because they might put you in a different box.

Parents of Autistic children are also at an increased risk of fabricated and induced illness (FII) allegations. Parents recognise the needs of their children, and recognise them as Autistic children, but professionals don’t. Instead they assume the child’s distress or behaviour is a result of poor parenting, and that the parent is trying to deflect that onto a diagnostic label. This is a narrative that professionals need to be aware of and avoid falling into.

“Evidentially, in every measure, life outcomes for Autistic people are, on average, significantly poorer, than those for non-Autistic people.”

This is what masking is leveraging. Masking isn’t causing these things. It’s our response to the stigma that we receive, the belief that we are broken people, the belief that we are disordered or that we have a condition. Disorder and condition mean the same thing - condition is not a better word. It means that we’re diseased, that we are dysfunctional, and it’s why we don’t use either of those words to refer to autism.

The way we are treated as Autistic people leads to significantly poorer life outcomes. A contributing factor is the energy we’re forced to pour into trying to keep ourselves safe from persecution. There are persistently identified barriers to education, healthcare, social care and employment for Autistic people. There’s a persistently identified likelihood of isolation, depression, Autistic burnout, extreme rates of poor mental health, and extreme rates of suicidality for adults and children. The biggest three killers of Autistic people outside of epilepsy are heart attacks, strokes and suicide. Those are signs of a stressed life, and a disproportionate amount of effort being put into existing.

Recent studies suggest that Autistic people without learning (intellectual) disabilities die on average 12 years younger than the general population. Studies are limited in what they can measure, but it speaks to a narrative. Masking is a lever to protect us from this, but it’s also a lever which causes us harm in the longer term.

These are a few examples of some of the ways in which we project acceptability in childhood; how that might continue into adulthood; and possible consequences of that. You might recognise aspects of yourself in some, none, or all of them. None of this is about self-blame. Masking is largely unconscious, and it’s about survival.

Mati Boulakia-Bortnick, The Autistic Coach, simplifies and summarises masking as getting your short term needs met at the expense of your long term needs. These examples are a nice illustration of that. If you’re the teacher’s pet, for example, you’re likely to avoid negative comments and punishment - from the teacher at least. And at work, people are likely to think you’re a great colleague if you’re taking the load off them. In the short term, it can be a great strategy and way of being acceptable to those around you. But it’s putting you on a path to be exploited, burned out and discarded in the long term.

These are some of the different domains of masking that Kieran and other researchers have highlighted, and some of the potential outcomes that might result.

Some of them you might recognise, either from personal experience or from reading and learning, and others might be new. You might find these are good jumping off points for delving into your mask, and we’re going to look at some of the ways in which we can start to potentially foster a safer, more authentic identity, which touch on a lot of these domains.

Most people have no conscious idea of what ‘Autistic’ might actually look like, and Autistic people are infinitely variable just like every other neurotype. There’s no off-the-shelf Autistic identity available to swap for the mask, and things can go wrong when people try to do that.

It’s very common for Autistic people, particularly those with lower support needs, to be assumed to be neurotypical by many of those around them in day to day life - even when they’re being treated poorly for being different. Neurotypical is treated as the default unless stated or visibly otherwise, even though neurotypical absolutely isn’t the default and isn’t the ‘correct’ way to be. When you consider the enormous range of ways in which someone’s neurocognitive functioning can diverge from the constructed standard, the majority of people aren’t neurotypical either. Younger generations are recognising this, with a recent survey showing that a majority of Gen Z participants identified as neurodivergent.

If we’re unmasking, then being aware of the existence of neuronormativity is really helpful. Sonny Jane Wise defines it “as a set of norms, standards, expectations and ideals that centre a particular way of functioning as the right way to function. It is the assumption that there is a correct way to exist in this world; a correct way to think, feel, communicate, play, behave and more.”

Learning about and challenging neuronormativity, and acceptance of neurodivergent ways of being as equally valid, can help build the self-acceptance that’s necessary for unmasking.

What follows are a few of the different ways you might like to start looking at what unmasking might entail, in a way that feels safe for you. There’s no right way to do this, it’s incredibly individual, but these are some ideas that might help, particularly if you’re struggling with where to start.

Connecting with Autistic community in a way that feels right can give you the space to learn about yourself alongside others with the same identity.

There are an amazing range of online forums and live groups for everyone from Black Autistics to late-identified people, to queer Autistics and Lego fans. Neurokindred run lots of these, and there are other organisations around the world also offering opportunities for connection. Some of these are listed each month in Jade’s Neurodiversity Newsletter. In many areas there are also local groups that run in-person meet ups for Autistic or neurodivergent people.

Learning about Autistic identity from well-informed neurokin can make it so much easier to understand yourself and your mask. Neurokin are people who share your neurotype, so if you’re Autistic, then other Autistics are your neurokin. These connections tend to be particularly important for Autistic people because of differences in social and communication styles compared to most allistics.

Studies have demonstrated that Autistic people communicate more effectively with each other than with non-Autistics. Humans have a need to be accepted and understood, so it stands to reason that Autistics who bond with their neurokin are more likely to get this need met. It’s why comments like “Don’t let autism define you,” are so damaging. Firstly, there’s nothing wrong with being Autistic, and there’s nothing wrong with someone deciding it’s an important part of their identity in the same way they might with anything else about them. And secondly, it risks cutting people off from the groups where they’re most likely to find kinship and safety.

This doesn’t mean all Autistics will automatically get on and be friends or will agree on everything, just as not all neurotypicals get on. Everyone’s an individual with their own likes, dislikes and personality. Those who share a neurotype are simply more likely to understand one another, which can be a really important foundation for the possibility of a genuine two-way friendship forming.

We’re not looking to fit in, but to belong. Fitting in involves changing yourself to be accepted within the confines of how you’re permitted to exist in a given space, while belonging is about being accepted for who you are. There’s a better chance you’ll feel a sense of belonging in settings that prioritise identities that are important to you.

Lots of us benefit from being in Autistic spaces, but being in one doesn’t automatically make it safe to unmask. There will be personality clashes, and Autistic spaces aren’t exempt from racism, queerphobia, or any other form of prejudice. It’s also the case that even if you do feel safe to unmask, you may still need to make accommodations for others even if they aren’t for stigma-based masking reasons. For example, your stim could result in sensory overwhelm for someone else, so you might need to switch stims in that space. Or your communication styles may not match, so one or both of you might need to adapt in order to have a meaningful exchange.

Whether or not you’re wanting to unmask around others, learning about yourself and figuring out what being Autistic means for you can be helpful for your wellbeing and how you navigate the world. You may not consciously be aware of your communication identity or sensory profile, for example, so learning about these and other topics can help you start to understand and integrate them.

Learning about your Autistic identity, and unmasking, are ongoing processes, and not something that can ever be completed. It’s a case of learning, unlearning, and evolving as new research and community knowledge comes out, and as you get to know yourself better.

If it feels safe to do so, then tuning in and listening to your body can provide clues as to how you would more naturally be if you’d never started suppressing your needs. For some people, particularly those with a lot of bodily trauma, then this may be best approached with a professional.

Almost all of us have been given the message that the way we hold or move ourselves is unacceptable in some way, whether that’s being told to look at people when you’re talking to them; to sit still; to sit a certain way in a chair; or to stop flapping your hands.

Scanning your body from head to toe and trying to notice what each part wants to do can be a way to start reconnecting. You might notice an urge to move in a certain way. To be in motion. To hold your body in ways that you’ve been condemned for. You might discover long-suppressed stims that feel good. If it feels ok then allow yourself to go with these. You might notice a shift in your emotional state, or like you are more connected with yourself - but it’s ok if you don’t. Reconnecting can take a lot of time.

Interoception is an internal sense which helps us feel and make sense of what’s going on in our organs, as well as other bodily sensations such as those linked with emotions. Interoception differences or trauma may mean this doesn’t work for you or doesn’t feel safe - and that’s ok. Whenever you’re doing this activity, or anything else, listen to your nervous system and only do what honours it.

If you struggle to feel or connect with your body but want to try, then testing out some different somatic practices could be helpful for you. It’s something you can do on your own if that feels ok, and there are lots of Autistic-created resources online. There are also plenty of Autistic somatic practitioners and educators out there if you’d prefer direct support.

Heavily linked with this is stimming. There’s a misconception that only Autistic people stim, and it’s fairly common for late-identified Autistics to think it’s something they don’t really do because they don’t rock or use fidgets.

Autistics tend to stim more frequently than allistics, but any form of sensory input and regulation can be stimming and it’s a universal human experience. It’s also not just about movement - it can involve any sensory input. For example, some people might be visual stimmers and spend hours immersed in patterns, art, or the flow of a river. Some might prefer listening to music or different types of sounds. Stimming can include things like dancing or tapping your foot, or viewing a beautiful sunset or the waves rolling onto a beach.

If you’re not aware of your stims then you’re probably doing some which are considered normatively socially acceptable without even realising it. Consciously noticing your responses to everyday sensory inputs and testing out different things can help you to discover and reconnect with what works for you.

There are an almost infinite number of different sensory experiences, so there’s no one way to approach this. Maybe you’re aware of which of your senses you tend to enjoy more than others, and which you find more difficult.

For some people, testing this out might look like buying a variety of different fidgets and seeing if any feel good to you. For someone else it might look like going for a walk and tuning in to the sights and sounds that regulate you. Other people stim with textures or tastes. Most use a combination. There’s no right or wrong.

Many Autistics move away from interests because they’re made to feel they’re too old for them, or that it’s wrong to be passionate about an unusual topic.

Delving into past interests may help some people to reconnect with their passions. Alternatively you may be well aware of the things that bring you deep joy, and the interests you can happily disappear into for days at a time. You may already be openly embracing these, or you may feel you need to hide them to avoid stigma and mistreatment from others.

Part of unmasking can involve reconnecting or being more open about these, if and when it feels safe to do so. For some people this links well with building connection with neurokin. There are online groups dedicated to just about every interest imaginable. You’ll also find online SpInfodump sessions where Autistic people take turns to talk about their interests, however obscure, and people share in the person’s joy regardless of whether the interest itself is shared. At its core, unmasking can be about feeling more yourself and experiencing security in that, so this can be a helpful part.

For some Autistics, particularly those you might meet online, Autistic identity itself becomes a passion. In some cases, you may find that your interests provide not just better connection to yourself and others, but the opportunity for more fulfilling work or volunteering.

If you’re struggling to conceptualise your unmasked self or you aren’t sure what’s really you, it can help to think about the traits that made you realise you’re Autistic. If you’re formally diagnosed then you’ll have some of these written down on your forms and in your assessment report. If you aren’t, then you may well have written some down anyway, and if you’re reading this then it’s a safe bet you will have thought about it.

As an example, perhaps you noted that you struggle with small talk, or simply don’t enjoy it or can’t see the point. Unmasking might involve not asking small talk-style questions that you don’t want to know the answer to, or giving an honest answer when someone asks you how you are. Maybe you’re overwhelmed by the complexity of different noises and constant chatter in your office. Unmasking might look like using earplugs or noise cancelling headphones instead of powering through.

Perhaps you feel best when you eat the same thing for lunch each day, but you’ve been told it’s wrong to do that. Choosing to listen to your needs and go ahead and eat the same thing if you want to is a form of unmasking. As with all of these ideas, it’s about what you want to unmask, what feels safe, and where.

The mainstream narrative around autism bears little relation to what it’s actually like to be Autistic. Autism is a social construct that has existed for just a century, pathologised in the form of distressed behaviours in the pages of diagnostic manuals. What psychiatry says constitutes autism is in a constant state of flux, and who is deemed to ‘have autism’ changes with each iteration.

From what historians have been able to piece together, Autistic people have existed since prehistoric times. Monotropic people are a natural part of the neurodiversity of human life. Exploring what makes you Autistic through a non-pathologising lens can be an extremely powerful way of re-authoring your story and identifying where you’re masking.

There are some excellent resources that can help you to do this, such as Aucademy’s website and Autistic Discovery Journey; AUsome Training’s Autistic Adults Welcome Pack; Reframing Autism’s Welcome Pack; Kieran’s website; and the Autistic Self Advocacy Network’s Welcome to the Autistic Community book.

Dr Luke Beardon’s golden equation of Autistic person + environment = outcome isn’t specific to masking, but it applies here too. You might not have control over many of the environments you exist in - or maybe you do. This includes not only physical environments, but also the people you spend time with, the things you do, and the systems you operate within. The degree of choice we have can vary enormously from person to person.

Changing environments, or tailoring existing ones to make them safer and more aligned with your sensory needs, allows you to unmask more easily. If you work somewhere that causes constant sensory overwhelm and doesn’t feel safe, you may want to build towards changing your workplace. It’s reasonably common for Autistic people to become self-employed because it might feel like it’s the most reliable way to get your more of your needs met and be able to drop more of the mask.

If your home is full of bright lights that blind you and textures that set you on edge then altering these might be a priority, particularly if this is a space where you have agency to make changes.

You may find some people particularly unsafe to be around, or they might only enjoy activities that drain you. Where possible, you might find you benefit from reducing the time spent with them.

Taking control of the things we can gives us space to unmask. Masking takes up an enormous amount of energy, so reducing the need to do so can lower our energy expenditure and decrease the risk of burnout. It allows us to be more conscious about how we might mask when we need to, while reducing the pressure where we don’t.

Setting boundaries that honour your sensory needs, communication style, monotropic nature and other aspects of Autistic identity can be liberating, but you may receive pushback from others. Unmasking in any form can lead others to accuse you of ‘regressing’, or putting it on, rather than recognising that you are revealing previously masked but very real aspects of yourself. But setting boundaries can be one of the hardest and potentially unsafe aspects of unmasking because it directly impacts others.

Masking can take the form of people pleasing and going along with the wishes of other people in a way that is detrimental to yourself, which may or may not be conscious. You might not have stopped to consider whether you want to spend so much time hanging out in places that overload your senses in ways you never recognised, and drain the social battery you didn’t realise existed.

People may have got very used to relying on you to do things for them, even when it causes you sensory overwhelm, meltdowns, shutdowns, and burnout. If you only recently realised you’re Autistic, you may not have had the language and framework to understand what was going on, and may have blamed yourself. Knowing that these are not personal failings, but natural Autistic responses to overwhelming and unsafe situations, can form a basis for exploring what is and isn’t ok for you as an individual. Your capacity will fluctuate with your environment, health, and everything else going on in life.

In the UK, counselling training is sometimes referred to as ‘The Divorce Course’ because so many therapists end up finishing relationships during their training. Learning about themselves, growing as people, understanding interactions better, considering patterns of relating, and setting healthy boundaries, can result in a mismatch. Some therapists end up being rejected by partners or friends who don’t like the way they’ve changed, or don’t accept the boundaries that have been set. Others choose to end some relationships themselves when they realise they weren’t healthy and that the other person isn’t willing to work on themselves. There’s a strong parallel here for many Autistics who discover their identity, start to work on themselves, and are either rejected or need to walk away from some of those around them.

Domestic abuse is something that is tragically prevalent against Autistic people. Research shows that nearly nine in ten Autistics who were assigned female at birth experience sexual violence at some point.

As Natasha Leahy puts it, “This heightened risk is not because autism causes abuse. Abuse always lies with those who choose to harm. The danger comes from unsafe systems, gendered violence, and the lack of autism-informed safeguarding and support. When the world misunderstands Autistic communication, minimises sensory needs, or assumes someone won’t be believed, it leaves doors open for exploitation and harm.”

A study found that only 1 in 4 Autistic people who reported domestic abuse were taken seriously. Many are blamed for masking, or not recognising red flags. Abusers often take advantage of Autistic traits.

Reflecting on your past through dedicated trauma exploration can result in immense personal growth, greater integration of self, and deeper understanding of your masks, but it’s something that’s likely to require proper support to be able to do that safely and reframe your story.

If you feel like you’ve already got the ‘low hanging fruit’ of unmasking and you want to start to lean into this yourself, then looking at how your rejection sensitivity shows up can provide a lot of clues. You might find your mask comes up harder when you’re feeling rejected, or believe you’re at risk of that. At its core, masking is about projecting acceptability, and rejection sensitivity is about feeling we’re in some way unacceptable, so they feed off one another.

Identifying your rejection sensitivity triggers gives you the opportunity to look at how you mask in response to those, but also why those triggers exist, and the traumatic experiences that have caused them. Working on these is likely to mean you feel the need to mask less in situations which would previously have prompted a thickening of your mask.

Sometimes we’re very acutely aware of particular identities we hold, but others less so. We might be unaware they exist; not have the framework or language to engage with them; not have seen some as relevant or a priority; been ashamed of them; or myriad reasons.

None of us are just Autistic. We tend to be multiply neurodivergent and have other disabilities and health conditions. We’re children, parents, friends, sports fans, artists, workers, citizens, and countless other identities. Picking apart your self-narrative and the labels given to you, and understanding the complexity of self, is a never-ending task. It possibly sounds too much. But being Autistic is not something it’s possible to separate from our environment, culture, trauma, social context, history, epistemology, hermeneutics, and countless other factors. The more we explore different aspects of self and grapple with the frameworks of varied disciplines, the closer we come to meeting our true Autistic self.

Many of us experience epiphanies throughout our lives when we learn about a new concept or identity and realise what an important role it plays in our story. In the moment it might feel like the whole story, but it never is. That’s not to invalidate or downplay the massive impact of learning you’re Autistic, but there will be other big lightbulb moments out there too if you’re open to seeing them. None of us will ever have the complete picture, but we can choose to uncover as much as we can, and not close ourselves off from future learning and growth.

So, what are the risks of unmasking? How do we balance that with the depth of exploration and growth available to us?

It’s helpful to acknowledge that there might be a pressure to unmask - it can feel like a demand, and lots of us don’t do well with those. This might be self-imposed because you value authenticity or you’ve read about the benefits, but there can also be enormous external pressure to unmask coming from some parts of the Autistic community. It’s a harmful myth that the degree to which someone unmasks represents how authentically Autistic they are. Unmasking often relies on having the support in place which allows people to do so.

When approaching unmasking, we need to consider if and when it might be safe to engage in that process. For those who are multiply marginalised, particularly racialised peoples and queer communities, the threats can be far greater. Starting to unmask can benefit our mental health; help us explore our Autistic identity; and feel more connected with ourselves – but the oppressive structures in our society mean it’s not a privilege that’s open to everyone.

You might experience ‘whiplash’ if your life involves moving between supportive environments where a more unmasked version of your self is welcome, and unsafe environments where you have to carefully manage your interactions. For some people unmasking will not be safe in any circumstances, and for others it may only be possible when alone.

Realistically our level of safety can change at any time - as we are seeing with the current situation in the USA where being openly Autistic is increasingly unsafe, and several other countries seem to be following suit.

You get to decide when, where, if, and with whom to unmask different aspects of your Autistic identity. You may have decided that it isn’t even safe to tell anyone in your life that you’re Autistic. Some people have accepting friends, family, communities, or workplaces. Others don’t have any of those things.

The word ‘privilege’ can get misinterpreted and put people on the defensive if it’s not something they’ve really explored. It’s not about trying to make anyone feel wrong for existing or holding particular characteristics. It’s an acknowledgement that sadly normative society values and privileges some groups of people over others, and that has huge real-life consequences.

You can view an example of a wheel of power and privilege here.

It illustrates some of the ways this looks. For the neurodivergence section, it’s talking about an individual’s proximity to neuronormativity, so how well they might be able to appear to adhere to neuronormativity and conform to societal expectations. As an example, someone who’s dyslexic is likely to have more privilege in that domain than someone who’s Autistic. And in turn they’re likely to be more privileged than someone with profound and multiple learning disabilities as it’s known in the UK, or profound intellectual and multiple disabilities elsewhere.

But it’s not as simple as that, because different identities intersect and weave with one another. Some people are multiply marginalised, while others hold relative privilege despite also having a marginalised identity. Becoming more consciously aware of how we’re privileged and marginalised is really important in terms of unmasking safely, because it’s going to have a big impact on where and when we might be able to take that risk. It can also help us to understand why other Autistics might find it easier or harder to unmask. And if we’re able to, then providing support for others who don’t share our privilege.

We are both speaking from positions of relative privilege as white and English-speaking British citizens. We can both communicate with mouth words, although we prefer to write. Kieran holds the privilege that comes with being male-presenting, while Jade holds the privilege of having a master’s degree. We each hold several marginalised identities and experience discrimination and oppression because of these, but these don’t erase the privileges that make it far safer for us to unmask than it is for a Black trans woman, for example.

Considering this with an open mind might can help you recognise other co-occurring experiences that you want to explore as part of your unmasking journey and identity work as well.

Whatever our privilege, or lack of, when we start to unmask we might find that those around us may respond in threatening, abusive, or even violent ways. Family or friends may view being Autistic as wrong, or have little understanding and think someone is putting it on. It’s sadly common for people to start to unmask and receive hurtful comments, pushback and worse from those around them. This is particularly the case where people have benefited from, or got used to, a compliant mask.

Some may have very stereotyped views of what it means to be Autistic, pushing anyone who is openly Autistic to mask in those ways to be accepted as ‘legitimately Autistic’, even if they don’t match their own experience. If you are multiply marginalised and experience stigma and discrimination due to people’s prejudice against your other identities, then revealing yourself as Autistic is unlikely to feel safe.

There are lots of memes like the one above that exist because it’s such a common experience. People discover they’re Autistic, start to explore what that means for them and what unmasking might look like, only to be met with “You’re putting it on,” or “You never used to be like this.”

When people learn they’re Autistic and read about facets of Autistic identity and culture, they often experience what gets labelled ‘skill regression’. This is a stigmatising term, and we tend to conceptualise it either as a part of burnout, or in the case of what we’re talking about here, the mask starting to crumble naturally with awareness. It’s a really common narrative that when people learn things about their Autistic self, there are bits they can suddenly no longer mask, or that take an enormous amount of effort to continue to do so.

Once late identified adults learn of our Autistic identity, we may become consciously aware of the harm of some of the environments we’re working in and the expectation to promote neuronormativity. This can expose an enormous mismatch between their values and identity, and what they have to do each day. Maintaining that part of the mask may be too much. Some people have the privilege of being able to leave and become self-employed or find a workplace that is more accepting. Not everyone has that option.

When the mask starts to crumble it can be easy to adopt new masks without realising by leaning into a perception of Autistic identity. Trying on facets of identity can be a really helpful part of the unmasking process and discovering what feels natural. Sometimes this can lead to keeping doing things that don’t actually feel natural, but become a new presentable Autistic mask, perhaps to deliberately avoid being perceived as neurotypical, or to feel acceptable in a particular Autistic space.

Burning out can also lead to aspects of the mask crumbling as the exhaustion and lack of energy makes it impossible to sustain. This sometimes opens doors or provides the impetus for people to lean into the adoption of a new, more sustainable identity. It might become that passionate interest, and lead to understanding yourself in a new light, but comes with that risk of adopting identities that aren’t necessarily yours. But who we are is constantly and naturally shifting, not just with our own self-growth and learning, but with natural processes such as ageing, changes in our health, or menopause.

Masking to some extent is unavoidable, so what you might you need in order to replenish yourself when you’ve had to mask?

Everyone has different energy levels, and masking can eat into our reserves significantly. If low energy is a challenge for you then energy accounting can be helpful, particularly if you know in advance that you’re facing a situation that will require heavy masking.

You might be familiar with the Coke bottle effect, which is a general concept in psychology to illustrate how repeated stressors eventually lead to dysregulation. If you shake up a fizzy drink and then open it, it explodes everywhere. Humans can experience a similar thing emotionally, and Autistic people are likely to find that a lot more things in their day contribute to shaking up the bottle, such as masking, repeated transitions, and sensory overwhelm. So if you’re masking a lot, you may need to relieve some of that pressure before it leads to a meltdown.

Interoception is something that can be improved to an extent, and the conscious awareness of tuning into your body if possible can also give you greater awareness of how you’re feeling, and how much capacity you have. Recognising what different situations do to your body is a great indicator of how heavily you might be masking, and can indicate a need to replenish yourself after being in stressful environments.

Stimming or immersing yourself in your passions might work for you. Perhaps you have particular rituals or routines, or like to lose yourself in a game or book. Extra sleep might be beneficial, or your favourite food, or exercise.

Tanya Adkin recently conceptualised Lilipadding. Monotropic people, which includes Autistics and ADHDers, focus more of our attention on fewer things at a time compared people who are polytropic and can more easily switch their focus. If monotropism is a new or unfamiliar concept then monotropism.org is packed with information and has a questionnaire which allows you to discover how monotropic you are. Kieran created this short video with animator Josh Knowles to explain the idea:

The neuronormative world we live in typically expects people to be polytropic. Think of school where children are constantly expected to switch their attention from one activity and subject to the next. Monotropic people trying to meet these expectations experience attentional trauma. The brain attempts to replicate the large amount of attention usually given to one thing, across many. Studies have shown that Autistic people create an average of 42% more information than allistic people at rest. Trying to operate in a polytropic way while using so much more energy eventually leads to burnout.

When monotropic people are forced to operate in polytropic ways it can be conceptualised as monotropic split. This enormous cognitive load frequently leads to meltdowns or shutdowns, so the relational practice of Lilipadding is designed to reduce transitional trauma. It offers a bridge instead of sudden collapse, allowing continuity to be maintained, and honouring monotropic ways of being.

Our societies run on enforced conformity. Everyone who possibly can is expected to ‘just get on with it’ – whatever the cost to them. We all have work we can do on ourselves, but no one can exist wholly outside of these systems.

Neuronormativity privileges ways of being that are most suited to providing a steady supply of the obedient workers needed for a capitalist system. Those who fall outside of this are likely to be punished in myriad ways and forced into the box - or discarded.

As Autistic people, we have limited agency to stop masking, but society as a whole has the choice to curate environments where it’s no longer necessary. It’s common to be dismissed and told that everyone masks. But if that’s the case, that only serves to prove that society’s existing systems aren’t healthy for anyone, and need to change. It shouldn’t be a personal struggle.

Those with power to change things have a responsibility to do so for those who don’t have that capacity. If someone feels unsafe and needs to mask to protect themselves, those with power are responsible for changing those environments. By continuing to learn about our Autistic identities and challenging pathologisation, we can help to spread those liberating narratives that make the continued dominance of neuronormativity untenable.

Autistic Masking: Understanding Identity Management and the Role of Stigma by Amy Pearson and Kieran Rose offers a deep dive into the academic narrative and research.

An Introduction to Unmasking Autistic Identity Safely: Things to Consider and How to Start by Jade Farrington takes a quick and accessible look at some of the themes covered above.

Download Delving Into the Complexity of Unmasking Safely as an ebook below

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Jade’s Neurodiversity Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.